Evolution of ϕText

According to Wikipedia, in August of 1988, Joe Becker (an employee of Xerox) published a draft proposal for a character encoding system to be called “Unicode”. The main purpose for that effort was to digitize the world's written languages for electronic publishing. It is now the standard for representing text on the World Wide Web. Unaware of that development at the time, during that same month (amazing!) I began work on developing a text system for an advanced programming language. Its purpose was to provide a rich text environment for creating source code documents with a larger character set than is in ASCII. Source code files would have more of the look and feel of word processor documents than plain ASCII text that is the general rule today. I now call it ϕText1. As a C programmer (since 1985), it had become obvious to me that Dennis Ritchie had run out of characters when defining the C programming language. ϕText1 defined a 32-bit “Flat Character” that would serve as the basis for representing a single character. The low-order 11 bits encoded 2048 displayable symbols while the upper 21-bits was used to encode text properties.

ϕText1 established a scheme in which a series of flat characters were encoded into a byte stream. For ASCII characters, the high bit was clear and needed no further encoding. All other characters (along with their text properties) were encoded using a sequence of two or more bytes beginning with a byte with its high bit set. The other bits were used to identify what was being encoded. This system solved many problems including the byte-endian dilemma. The algorithm was inherently self-synchronizing which limited data loss caused by corruption in the data stream. I now call it ϕTSE1 for “ϕText1 Stream Encoding”. I wrote the first text editor (called ϕEdit) that implemented the encoding scheme. Programmable characters were displayed on a Hercules Graphic Plus board running on MS-DOS in an IBM-compatible PC (Model XT clone). Editing was done using the Flat Character format but they were stored using ϕTSE.

Over time I became aware of Unicode. In 2009 I decided that ϕText needed to become Unicode compatible. Using the same encoding algorithms I had developed for ϕText1, I redefined the system so that the 32-bit flat character would accommodate the much larger Unicode Code Point. The new Flat Character has a 21-bit Symbol Code and that leaves only 11 bits for Text Properties. Gone were the Background Colors among other things. But it turned out to work pretty well. I now call this new system ϕText2. Since I now consider ϕText1 to be obsolete, I just call it ϕText.

ϕEdit Version History

Since 1988, ϕEdit has gone through six generations. Gen 1 used the Hercules Graphic Card Plus running on MSDOS. Gen 2 used the Hercules InColor Card. It was the first to show colored text. Gen 3 used an IBM VGA card and it still ran on MSDOS. Gen 4 was the first version to run on MS NT 4.0. It still used bit-mapped fonts so the printout didn't look very good. Gen 5 was the first version to use TrueType and OpenType fonts. It was buggy and needed rework of its data structures. It didn't support the different character sizes. Gen 6 is the version I use now and it supports all of the text sizes, colors, styles and attributes as well as paragraph formatting.

ϕText Flat Character Format

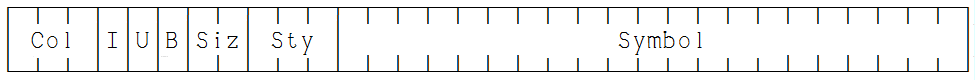

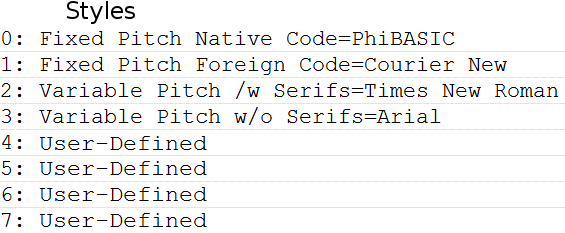

The ϕText Flat Character is the form in which individual characters are processed. It is a 32-bit value composed of a number fields. The lower-order 21-bit Symbol represents the Unicode Code Point. Next is the Style field that determines the type face of the character. The Size field stores one of four sizes. Next are the three Attribute bits that can be individually set and cleared. These are for Italic, Underscore and Bold. Finally there is the 3-bit Color field. This gives your text one of eight foreground colors. Background color is always assumed to be white as printed on paper. They are similar to the resistor color codes. Each field value and its meaning are tabulated below:

Paragraph Formatting

ϕText supports four kinds of paragraph

formatting as you will find in most word processors. These

are:

1. Left Justified

2. Right Justified

3. Centered

4. Fully Justified

Line Wrap

ϕText allows for lines to be up to 255

characters long. Lines longer than this will be wrapped

using a Line-Continuation terminator. This permits

paragraphs with indefinite length while keeping text on

lines within a reasonable horizontal viewing range.

ϕEdit has a parameter that controls where a line should

wrap. It provides a command that normalizes the number of

words on each line using word wrap. This automatically

inserts and deletes line continuation codes so as to make

text fill available width. When importing UTF-8 files,

New-Line characters become End of Paragraph Left

Justified. When encoding a ϕText file to UTf-8, line

continuation codes are removed and all end of paragraph

codes are converted to Newline characters. Paragraph

formatting is lost. This is one of many reasons why source

code is generally kept in ϕText format instead of UTF-8.

ϕText Encoding and Decoding

A sequence of flat characters can be fed

into a ϕTSE (or UTF-8) encoder for storage in a file or even

memory. The output is a zero-terminated sequence of bytes.

The same sequence of flat characters can be recovered by

feeding the same byte stream into its paired decoder. Both

ϕText and UTF-8 encoded byte streams are self-synchronizing.

That keeps the encoder and decoder synchronized so that, if

there is data corruption in the encoded byte stream, the

decoder will quickly lock onto the beginning of the next

character. The basic encoding methods for ϕTSE and UTF-8

have the same efficiency when compression in ϕTSE is

disabled. But when compression is enabled, byte streams

generated by ϕTSE can be much smaller.

Three Kinds of Compression

These are:

1. Repeated CharacterWhen text is all ASCII, the only compression that is realized is Repeated Character. This includes space characters. When an end of paragraph is seen, the character that is assumed to be seen last is the space character for the upcoming line. Character indents are done with repeated spaces. Any amount of repeated characters on a line is encoded in a 2-byte sequence. 3 or more non-space characters in a row are also compressed using the same method.

2. Recently Used Symbol

3. Recently Used Symbol Page

ϕTSE remembers the last 32 non-ASCII symbols that were seen last in the character sequence. They are replaced with 1-byte encodings in the byte stream. Also, ϕTSE remembers the last 32 "pages" of symbols that were seen in the byte stream requiring 3 or 4 byte encodings. A "page" is 128 characters. When seen again within that window, the symbol is encoded with a 2-byte encoding. Both compression algorithms maintain a least recently used sequence. When a new element is encountered, it replaces the least recently used one.

When compression is enabled, typical files can be 20% to 40% smaller than their non-compressed counterparts or more. Without compression and for files that contain only ASCII, ϕTSE generates roughly the same file sizes as UTF-8.

Programmers have suffered from a number of problems with the ASCII codes that control where text is positioned within a text document. Tab codes are not used. Instead, indents are implemented using space characters. When compression is enabled, indents can make ϕText files considerably smaller than their UTF-8 counterparts.

Control Codes

Originally, control codes were defined to be used with teletype machines that are mostly obsolete. For this reason, ϕText adjusts the definitions of several of the original ASCII control codes for its own purposes.New Line and Carriage Return

Stateful vs Stateless Encoding and Parsing

There are great benefits to having source code files that have the look and feel of word processor documents. Much of the information in such documents can only be efficiently recorded using stateful encoding. When text attributes such as underscore, bold and italic are used, almost invariably they are applied to consecutive sequences of characters. These can't efficiently be stored using stateless encoding. The same applies to the other text properties such as Size, Color and Style. These are almost always applied to consecutive sequences of characters. Recording these statelessly would cause their byte streams to explode in size. Also, compression algorithms are inherently stateful because they make use of most recently seen characters in the data stream. Indeed, this information accounts for most of the state information used in the encodings.

There are really only two benefits to having stateless encoding. One is to limit the amount of data that is corrupted when an error appears in a byte stream. The other is to limit the amount of state information that has to be recorded at each point in a character sequence where a parser may want to roll back to an early part of a byte stream. Historically, the greatest risk of errors comes from transmission of data along wires that are subjected to noisy environments and read errors in mass storage devices. Main memory errors are a much more serious problem whether stateless encodings are used or not. But modern systems have so many layers of invisible error recovery that we generally don't have to worry about it much.

ϕTSE uses stateless encoding for the symbols that explicitly appear in byte streams so that part of the encoding is just as immune to errors as is UTF-8. It is the text properties and compression codes that are more likely to be altered beyond the actual data that was corrupted. But those don't even exist in UTF-8 so the two are not comparable in that way. Say you were to lose all text properties in a worst case scenario. That is arguably no worse than having none in the first place which is what you have in UTF-8. As for the compression of ϕTSE that does not exist in UTF-8, any loss of information is limited to the current paragraph because ϕTSE clears its buffers and starts over at the end of every paragraph. This reduces its compression effectiveness. But limiting loss to the current paragraph will minimize data loss when disaster strikes. Most compression algorithms will just throw up their hands when the level of corruption exceeds a thresh-hold. But ϕTSE can give you a considerable amount of uncorrupted text to work with when some of the text is lost. It should be clear that there are over-whelming benefits for using ϕTSE over UTF-8 for storing source code in files.